Unlocking the secrets of town's ruined castle

In 1830, William Woodman found Norman carved stones on the east side of Ha’ Hill. The tiny pictures on p.20 of Hodgson’s History of Morpeth show the capital of a column and a billet moulded segment of an arch, possibly from a chapel.

Then, in 1999, Lancaster University Archaeological Unit made a contour plan of the hill at one metre intervals. This showed the existence of an artificial platform in the same area, being the probable site of the castle keep.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMost of the castle would have been of timber, however, and it may be that if a full-scale excavation were carried out, trenches and post holes for the palisades and timber uprights would be revealed.

It is generally assumed that this was the castle that King John burnt in 1216, and likewise, that it was after this that the De Merleys rebuilt their castle on its present site.

The Normans and their medieval successors were energetic builders. If a castle or a church was needed, they got on with it.

A castle was, indeed, essential for a medieval baron, for although a place like Morpeth could not hold out against the King, you still had to be able to defend yourself against lesser enemies.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut a castle was more than just a fortress. It was also the baron’s family home and his administrative headquarters.

And, not least, a sign of his status. A baron without a castle wouldn’t be much of baron.

Once Roger De Merley II had made his peace with John’s successor, Henry III, which he did in 1218, the new castle would have gone forward at a rapid rate. In short, the present castle is almost certainly of 13th century date.

It is best to study it in two parts, first the castle at large, then the gatehouse.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

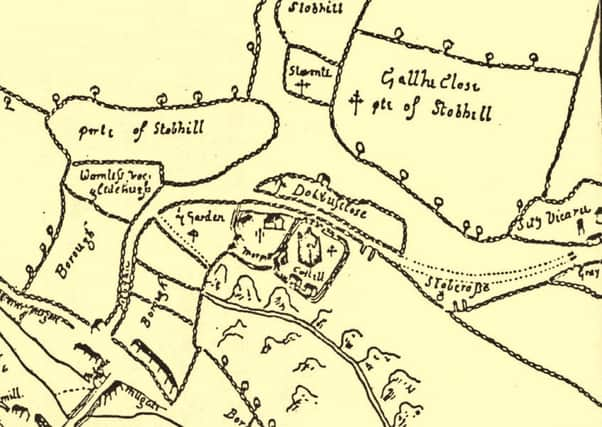

Hide AdOur best evidence for what the castle was like is the 1604 map of Morpeth. It is primarily an estate plan so that the lord and his agents could be certain which were his lands and which the corporation’s.

East is at the top. The road going off on that side is Shields Road, and the one off to the right, the road to Newcastle.

Pictorial symbols are much in evidence, but they are not explained, nor are they used consistently. Thus, the little hillocks with what looks like a road between them are actually the Postern Burn, which divides the old castle from the new. The rows of chain-stitch are field hedges, some of which have trees in.

Apart from a short section of the high road to Newcastle, roads are not shown.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis is not a mistake, it’s what it was like. Fields and closes were fenced, roads not. The road was just the wasteland between the closes.

The empty space above Dolbus Close, however, was not a road. It was the steep and uncultivable valley of the Church Burn, represented now by Deuchar Park.

The castle has two baileys, the outer bailey on the left, with a substantial house and a row of cottages or sheds, and the inner bailey on the right.

The tower, or keep, stands in the middle of the inner bailey, with a few outbuildings below it, i.e. on the west side.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe gatehouse is shown as a much smaller building, which gives us some idea of how imposing the tower must have been.

The best way into the castle grounds is on foot, by way of an entrance behind the War Memorial.

A stony track leads into the outer bailey, from where there are fine views of the town. You approach the gatehouse by a path with an attractive grass strip down the middle. Most views of the gatehouse are taken from this side.

The outer bailey, presumably, once had a wall all round it, but all that is left now is an imposing fragment. It isn’t all that easy to see because of the trees and shrubs, but we show it caught by the winter sun when the leaves were off the trees.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is thought that this wall formed part of the barn where Montrose placed his cannon during the siege of 1644.

You enter the castle proper though the gatehouse. Our picture shows it from inside the inner bailey. The single storey building with the red door is a modern stable block, built in the 1860s when the 7th Earl had the gatehouse refurbished as a residence for his agent. We’ll look at the gatehouse in another article.

Walk past the gatehouse, through the gap in the hedge, and you find yourself in the inner bailey. This is referred to in an old document as the garden, and that is how it is maintained now, though purely as an ornamental one.

It was probably here that the starving Scottish prisoners from the Battle of Dunbar were corralled in 1650, hundreds of whom died from eating raw vegetables to allay their hunger.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis is also where the keep, or tower, once stood. No sign of it now. I can’t even find that anybody has surveyed it geophysically, for example with ground-penetrating radar, though archaeological dowsing might produce equally good results.

The wall of the inner bailey is almost complete in the sense of going most of the way round, but much of the facing stone has been robbed out, leaving only the rubble core.

This rubble-work is probably original, of the mid-1200s, but rubble isn’t dateable. And in any case, the whole fabric of the castle and gatehouse has gone to ruin and been repaired many times in the past 800 years.