Village's 69 years of life saving at sea

Thus, in November 1861, the Committee of Management awarded the Institution’s Silver Medal to Mr Thomas Brown of Cresswell, together with a small reward for himself and his three sons, for rescuing the entire crew of six of the schooner Julius, of Aalborg.

Mr Brown was known as Big Tom, and since all the men of the Brown family were noted for their huge size, he must have been an absolute giant. In a daring piece of seamanship, he brought his coble alongside the stricken vessel. Then, seeing a big wave bearing down upon the wreck, shouted to the crew to jump, and got his boat away just before the schooner was smashed to pieces.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe incident that led to the setting up of the lifeboat station was the death by drowning of Tom’s brother James, and James’s three sons, in 1874. They had gone out in fine weather at 6am, but were caught by a sudden squall as they returned. Despite the long tradition of saving the shipwrecked, the inquest found that there was no life-saving apparatus at Cresswell, and no barometer which might have given warning of the impending bad weather.

Cresswell was a lifeboat station for just under 69 years. The Old Potter, which served from 1875 to 1889, was launched eight times and saved 33 lives. The Ellen and Eliza, 1889-1909, was launched 20 times and saved 41 lives. The Martha, 1909-1944, was launched 30 times and saved 17 lives. None of them was motorised, though the Ellen and Eliza, of which there is a ship-in-a-bottle model in Cresswell Village Hall, had sails.

Masts and sails were not necessarily an advantage. The village and lifeboat house stand at the top of a low cliff so there was no question of launching the boat directly into the sea. Whatever the circumstances, she had to be dragged over the dunes and sometimes a long way along the beach to a suitable launching place.

“On December 24, 1889, the new lifeboat ‘Ellen and Eliza’ was launched on receiving a report from the Coastguard that a steamer was ashore about a mile south of the Lifeboat Station, during a strong south-easterly wind and a strong sea. The SS Cerdic of Newcastle bound from Christiania for Newcastle, in ballast, was found stranded on Headagee Rock with her fore-hold full of water. The lifeboat laid out an anchor and took a telegram and letter ashore, returning at once to the vessel and remaining in attendance on her. At low-water the steamer’s crew went ashore, the ship being then dry, but the Master and three other officers remained on board, the lifeboat remaining by her until an hour after high-water. The vessel ultimately became a wreck.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the naming of the third and last lifeboat, the Martha, the District Inspector of Lifeboats said that she was of the self-righting Rubie class, named after its designer, who was Surveyor of Lifeboats to the RNLI.

The self-righting Rubie was designed specifically for places like Cresswell, “where they had to launch on an open beach and frequently in heavy gales... they required a light boat and facilities for quick despatch over heavy sands”.

He described Cresswell as “quite unique in the lifeboat service”.

“It was a very small village and whilst there were enough men to form a crew, there were not enough men to act as launchers of the boat. He added that the task of launching a lifeboat over an open beach entailed, in heavy weather at all events, great fatigue, exposure to cold and even danger.” (Cresswell Lifeboats).

Even so, the Martha weighed nearly two-and-a-half tons.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne of the most striking things is the length of time the crew were out, often following an exhausting session getting the lifeboat into the sea, and getting drenched in the process: “On February 6, 1899, in keen frosty weather accompanied by a heavy sea and thick haze, the lifeboat went to the assistance of the steam trawler ‘Lapwing’ which was observed stranded on the Broad Skear Rock...the lifeboat remained by her until...the tide receded and the crew of eight men were able to walk ashore, carrying their effects with them.

“One of the lifeboat-men, Henry Jefferson Brown, had a slight cold and he got very wet in getting into the boat. After being at sea in a keen frost for three hours, he later developed pneumonia from which he died on February 28. In April of that year, the RNLI Committee of Management voted £250 to his widow and five children.”

Similarly in October 1928, the steam trawler Darwen, of Fleetwood, ran ashore three miles north of Cresswell. The wind was strong south-easterly with a very heavy sea. The lifeboat was launched at 6.45am, took a man off to pass a message to the ship’s agent, brought him back, and stood by until about 7pm, a 12-hour stint in an open boat.

The Cresswell lifeboat’s last call-outs were on March 13, 14 and 15, 1941, to assist the SS Empire Breeze. The Empire Breeze had already been damaged on the Bondi Carrs, and was under tow. The tug struck a mine in Druridge Bay and sank. Four men in the boiler room were badly scalded. The Empire Breeze anchored and the tugboat men were taken aboard.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCresswell was called out at about 8.30pm, but a special gap in the coast defences north of Cresswell had been inadvertently filled in. The army removed the barbed wire and concrete blocks, and the Martha was launched at 11.20pm. She landed the tugboat crew at Cresswell at 1.15am.

Then, shortly after 3am, they were asked to stand by the casualty. She was anchored in a minefield and taking water. The crew needed taking off if pumping failed, and tugs could not reach her until a channel had been swept. The lifeboat stood by for 16 hours until 8.30pm, and was called out twice more, at 1.10pm and 10.15pm on March 15.

There were no more launches, and the station closed in 1944, partly because it was becoming difficult to find enough men to make up a crew in wartime. The other factor, which Mrs Mitchell suggests somewhat cautiously, was that Amble and Newbiggin, with only about 12 miles between them, both had motor lifeboats, giving them a higher speed and longer range.

This is an ongoing trend. Amble’s current Mersey class lifeboat has a top speed of 17 knots and a range of 240 nautical miles, but they are raising funds for one of the new Shannon class, which can travel at 25 knots and has a 250 mile range.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

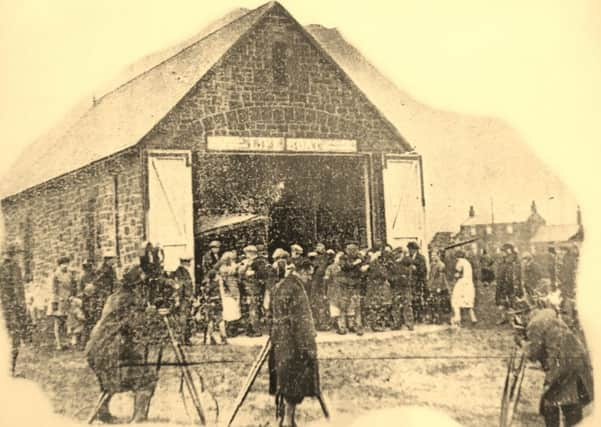

Hide AdAfter the war, the lifeboat house at Cresswell was used by the Women’s Institute, and in summer by the St John Ambulance. It was thoroughly converted in the 1990s to make it into a proper village hall, and now has a handsome viewing lounge looking out to sea.

But 140 years ago, it was the lifeboat house.

Source: Jill Mitchell, The Story of the Cresswell Lifeboats, 1986. For information on the Rubie class lifeboat, see www.seahouseswebsite.co.uk